There’s an interesting game often played at social gatherings called ‘2 truths and a lie’. It is simple: I will give you 3 statements. 2 of them are true. And 1 is not. You have to identify the lie to win the game.

Let’s play 2 truths and a lie via this article. I will make 3 statements. I will argue for each of these statements. Arguments will have facts and interpretation. Facts are all true. Interpretations are mine. You pick which 2 statements you want to pick and which one you want to discard.

Ready?

1. Supreme court conducting hearings on video-conferencing translates to wider access to justice and democratizing it

The Courts across India have taken several measures to work during this lockdown. Firstly, they are confining themselves to only hearing matters that are considered urgent. Secondly, they are using video-conferencing and other digital means. Thirdly, they are developing e-filing modules for contactless hearings. All of this in an attempt to have limited physical interaction with the litigants, lawyers and judges, and also to reduce congestion in Courts. This is being done under the aegis of the Supreme Court E-Committee.

The pandemic has shown us that justice isn’t curtailed by four walls. Anyone can knock on the doors of the Supreme Court from thousands of kilometres away. And as we work towards rebuilding our society post the COVID-19 era, it is worth considering the continuation of virtual hearings in addition to in-person hearings. So as to make the Supreme Court a more inclusive and accessible institution for enforcing our rights.

Did you know? There is a direct co-relation between the state’s distance from the Supreme Court and the cases that make up the docket of the Supreme Court.

Research shows a very interesting observation. The closer a state is to the Supreme Court, the more are the cases from that state in the Supreme Court. A study carried out by Nick Robinson shows that appeals from the Delhi high court to the Supreme Court outnumbered the appeals arising out of the high courts in Kerala, Gujarat, Assam and Jharkhand combined, in 2011, and this trend has continued ever since. Enabling remote access to the Supreme Court can remove this geographic barrier to the Supreme Court. Thereby ensuring wider access to justice in the Supreme Court!

Here’s another argument.

Before the lockdown, India saw more and more cases in the Supreme Court being filed by groups or individuals who are, at best, public-spirited individuals (read: PILs). By those having no actual connection to the rights violation or dispute. This in turn has led to those who are actually and materially affected on the ground being denied their day in court out of a double whammy. Firstly, they cannot afford to go to Delhi. Secondly, their parent high courts are hesitant to hear their cases. This is because they raise questions already pending in the Supreme Court.

The removal of those suffering a violation of their rights from the process of adjudication altogether, on account only of geographic proximity to the Supreme Court, translates directly into rendering those outside of Delhi voiceless. It can also lead to ineffective and impractical solutions to complex legal problems. This is mainly because contextual nuances (which can be gathered from hearing those who are actually affected), cannot be obtained from the public interest petitioner. By enabling online access to the Supreme Court on a permanent basis, those most acutely in need of enforcing their rights are more likely to be heard. Thus moving from a paradigm of problem solving from a distance to problem solving in proximity.

And here’s the last argument for my first statement of this round of ‘2 truths and a lie’. Permanent online access to the Supreme Court can have the effect of democratizing the law-making process.

Through powers granted under Section 32 and 142 of the Indian Constitution, the Supreme Court has been involved in several matters where judgements translate into judicial law-making. Such amendments have far-reaching consequences on people across the country. However, participants in this process are confined to the judges of the Supreme Court, members of the Delhi bar, and public interest litigants in Delhi. It is rampant that representation of stakeholders located elsewhere in the country are nowhere to be found in this process. Permanent online access to the Supreme Court will enable better involvement of stakeholders from a variety of socio-cultural, and economic backgrounds, be it lawyers or litigants, or even the general public. Thus, directly translating into expansion of the democratic pie.

2. Machine-led outcomes are establishing to be more accurate than human judgements

A while ago, a computer software, AlphaGo (an artificial intelligence program), defeated the best human player in an ancient board game called Go. In Go, opponents take turns placing black and white stones on a 19-by-19 grid. They try to surround each other’s pieces and claim territory. This chess-like game is considered to be one of the most complex. Mainly because of the number of moves and probabilities involved. This was a landmark achievement in the world of computing. It proved the potential of a machine to become truly ‘artificially intelligent’.

Extrapolate this to the legaltech world. Does this translate into dehumanized decision-making?

Multiple studies and demonstrations have been conducted by legaltech enthusiasts across the globe. Which have resulted in a similar outcome. That is, the risk in error of judgement is far lower in machine led outcomes vis-à-vis humans. Let’s simplify this. Chances of the machine going wrong in giving the judgment were much lower than chances of a human going wrong in delivering the judgement. These demonstrations were based on the machines analysing past judgments. And applying those principles and outcomes to situations thrown at them.

(Here’s a simplified example of how machines can be trained. To train a computer to spot the difference between cats and dogs, the system is fed pictures labelled “cat” or “dog”. This is done until the algorithm is able to make that distinction on unlabelled pictures.)

Machine learning has been successfully tested and implemented for stock predictions and is poised to revolutionize the legal framework globally. It has the potential to analyse the available legal data. And then make predictions of the legal outcomes out of it, even better than humans can. And the next logical step is to actually give out a legally binding judgement!

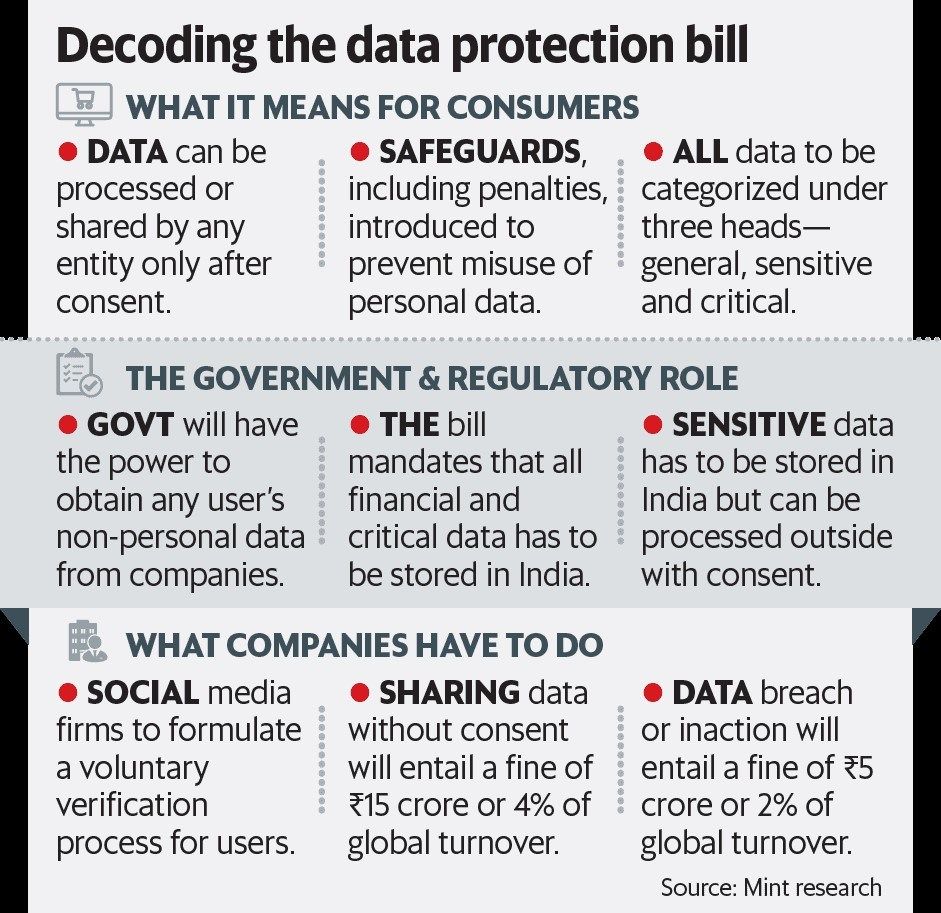

3. India’s proposed data protection framework proposes to strike a balance between data privacy and fostering growth in the country. But, in fact, it strengthens the state at the cost of privacy

In a landmark judgement, Justice K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India, in 2017, the Supreme Court included the right to privacy as a fundamental right. And it included informational privacy as a subset of this right to privacy. Up until this time, privacy was considered only when there was a violation of it. And not a right requiring protection. This judgement turned the tables and made the right to privacy as a right that requires protection (irrespective of violations). And in order to establish a framework to this end, in December 2019, the government introduced the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019, in parliament. Which would create the first cross-sectoral legal framework for data protection in India.

The bill aims to protect the informational privacy of individuals.

By creating a preventive framework that regulates how businesses collect and use personal data. Consequently, it focuses primarily on regulating practices related to the use of data. A complex and of course, large list of compliances is contained in this bill. Which is applicable for both, large as well as small companies. These compliances include the data the companies are collecting, how and why are they collecting it, where they will store it, how will they use it, who will they share it with etc. (And btw, the cost-benefit analysis of such compliances is yet to be measured!)

Finer prints reveal that this bill also contains provisions that allows the government to compel businesses to share non-personal data with them. This could have deleterious consequences. Additionally, the bill allows the government to exempt any of its agencies from the requirements of this legislation. Furthermore, it allows the government to decide what safeguards would apply (or not apply) to its use of data. This potentially constitutes a new source of power for national security agencies to conduct surveillance—and, paradoxically, could dilute privacy instead of strengthening it.

To summarize this round of 2 truths and a lie, here are my statements for you:

- Access to justice is limited to those in close proximity to the Supreme Court. Going digital means a level playing field from Kashmir to Kanyakumari, and democratization of justice.

- Jobs of judges are in danger, thanks to artificially intelligent machines who make fewer mistakes than them.

- The Personal Data Protection Bill does not necessarily protect personal data, it rather shifts the power from businesses to the government.

You pick those you believe in, and the one that you identify as a lie. Write to me at asialegaltech@gmail.com and let me know!

PS: Here’s the catch: what makes ‘2 truths and a lie’ appealing is that your choices less about the other person and more about your own beliefs.

Also read: Digital transformation trends swooning the world in 2020

Legal Tech Asia is now on Telegram. For latest updates on what’s happening in the legaltech world, subscribe to Legal Tech Asia on Telegram.